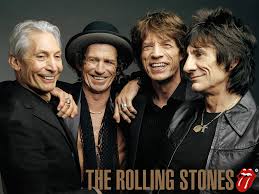

I was sweating acne and sporting bellbottom pants when I first heard the Rolling Stones’ song, “You Can’t Always Get What You Want.” Named the 100th greatest song of all time by Rolling Stone magazine in its 2004 list, it was written by Mick Jagger and Keith Richards and released in 1969 on the Let It Bleed album.

While not an actual “news nerd,” I confess a reasonable obsession with news and current events. To that end, my reading and listening of recent relevant happenings, leaves me walking around in a “you can’t always get what you want” kind of daze.

• Internationally, the ethnic and religious cleansing in northern Iraq by ISIS is being called “the Rwanda of our time” by Dan Hodges of The Telegraph.

• Nationally, the catastrophe in Ferguson, Missouri where yet another unarmed black teenager is killed by a white police officer is a cesspool of allegations and overreactions.

• Locally, I talk with another mother that has custody of a “heroin baby” and struggles constantly with a husband who refuses the tough love option of refusing to give money to his addicted kids.

• Then there is the blended family where an intelligent, but emotionally damaged 8 years old is using the guilt of her dad and the vengeance of her mother as kindling for the ongoing flash fire that may ultimately consume both families.

• And finally, there is the pastor of a small congregation who has spent almost a year gathering information for a courageous outreach into a depressed and needy community yet his sleep is interrupted by the explosive dynamic of staff relationships and congregational contentment.

All of these scenarios rock with the haunting reality of the Rolling Stones lyrical truth: “you can’t always get what you want.” And just as each situation bears closer analysis, so our song requires a closer listen.

The three topics discussed in the song address the hot button issues of the 1960s and 1970s: love, politics and drugs. (Hmmm . . . does this list look familiar to our previous observations?) Most significant is the pattern outlined in the song. First, there is optimism, then disappointment and finally, there is an acquiescent practicality that saves the day:

You can’t always get what you want

You can’t always get what you want

You can’t always get what you want

But if you try sometimes well you just might find

You get what you need

Is it possible that every experience of life can in some way be redeemed or reconciled in a way that exceeds the pop psychology highlighted in Breaking Bad’s fictional character Saul Goodman or as the writer’s intended it to sound, “S’all good man?” Is our collective response to life’s difficulties simply reflected in the flippant refrain of Bob Dylan’s song “It’s All Good”:

But there’s nothin’ to worry about

’cause it’s all good

It’s all good, I say it’s all good

Life lived with an honest sense of sanity and perspective and hope demands an answer to that question. Is it possible that the dark, desperate, and deeply unsatisfying moments of life can be honorably redeemed or are we simply left to dance the dance of denial to the melody of “It’s all good, I say it’s all good?”

The longer I live and the more I listen to the heartbeat of hurt and disappointment surrounding our world, both locally and internationally, the more I am convinced our only defense against the hardened cynicism of disappointment which left untended will result in life altering bitterness is the capacity to pay attention to what matters most. We hear it as children making our first steps, “pay attention,” we reflect on it as teenagers choosing our first friends, “pay attention,” and much too often we regretfully forget it as we make our first feeble attempts at adult life, “pay attention.”

I am not sure when I first heard or accepted it, but slowly I began to understand that life lived deeply and meaningfully is not simply choosing one path and pursuing it doggedly to the end. It has much more to do with how we pay attention and discern when to change paths or directions because the situation and circumstances allow and sometimes even demand it. Life lived on the far side of disappointment and bitterness is the result of responding with grace and faith when our journeys are interrupted and left unfinished.

This becomes clear in the final line of the “you can’t always get what you want” refrain. It says, “But if you try sometimes well you just might find you get what you need.” The “trying” speaks to our need to pay attention and getting “what you need” identifies the opportunity for every part of life to be redeemed or reconciled in a way we may not want, but we ultimately need.

People of faith see this in the life of Jesus. Leonard Sweet says, “Jesus didn’t know any waiting rooms—he knew only living rooms.” His point is an important one, especially to those who live with the terror of time, always trying to get to the next place or accomplish the next thing in hopes of outrunning our sense of disappointment and bitterness.

While we spin our wheels in “waiting rooms,” Jesus insisted on moving every experience of his life into the “living room.” Every moment had meaning because Jesus knew the author and finisher of time. Every second had power because Jesus knew the creator and sustainer of time. Every day had potential because Jesus knew the maker and redeemer of time.

No, we don’t always get what we want . . . but if we pay attention and live with grace and faith, we can find our way to the “living room” where we might get exactly what we need! Thanks be to God.